| Before

I get to the specific example of the Seattle Empire,

I would like to talk about early twentieth-century laundries

in general. The commercial laundry industry was born

and rapidly matured in the late nineteenth and early

twentieth centuries. In the process, it developed its

own infrastructure of equipment manufacturers and distributors,

soap and chemical suppliers, trade associations, and

educators such as Lydia Ray Balderston, who published

a book entitled 'Laundering' in 1914.

The

title page credits Balderston as an "Instructor

of Laundering" at the Teachers' College of Columbia

University in New York City. She provides an in-depth

description of the laundering process, which basically

involved four steps. The plan

of a hotel laundry from a turn of the century magazine,

National Laundry Journal, illustrates the basic process. The

title page credits Balderston as an "Instructor

of Laundering" at the Teachers' College of Columbia

University in New York City. She provides an in-depth

description of the laundering process, which basically

involved four steps. The plan

of a hotel laundry from a turn of the century magazine,

National Laundry Journal, illustrates the basic process.

First,

the dirty laundry was marked to identify its owner and

sorted by fabric and type of item. Next, the laundry

was washed by large cylindrical machines, after which

the wet goods were transferred to extractors (see picture

above left) where moisture was removed by centrifugal

force. This is the equivalent of the spin cycle in modern

washers.

The

items were then dried, sometimes by being placed in

a heated drying room, and, finally, "finished,"

which might entail starching, ironing, folding, and

mending.

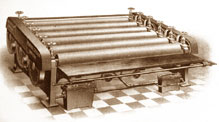

Right

is another central piece of equipment, an ironing 'mangle'.

Authors such as Balderston spent a good deal of time

describing the ideal facilities for both home and commercial

laundries. A few passages from her book outline the

main concerns associated with commercial laundry design: Right

is another central piece of equipment, an ironing 'mangle'.

Authors such as Balderston spent a good deal of time

describing the ideal facilities for both home and commercial

laundries. A few passages from her book outline the

main concerns associated with commercial laundry design:

"The

whole room or rooms should be built with the idea of good

ventilation and good light, and with every consideration

that will promote the best sanitary conditions...If

the plant is very extensive, it naturally must reach in

height, and in this case the division of department is

brought about by having each department on a floor by

itself. Height of building overcomes expense of land,

but of course involves expense of elevators and lifts,

as well as more supervision by heads of departments...The

windows in the laundry should be large, and for extra

ventilation a transom over each. This transom allows fresh

air to enter the laundry without the hindrance of this

air blowing directly on the work, which not only dries

the garment about to be ironed, but cools the iron...

"Driers

that are like rooms should be ventilated to allow

escape for moisture and steam, and to increase the

ventilation, those that do the most rapid drying are

equipped with an electric fan..."

"The

ironing section of the room should have good light,

because of the uncertainty of scorching clothes, as

well as being able to see when the wrinkles are ironed

out."

Some

general information on real - versus academically ideal

- laundry facilities is provided by contemporary government

reports. The coming of age of the commercial laundry

industry was in 1907, when it was found by the U.S.

Department of Commerce to be of sufficient importance

to merit an industrial census. Six years later, in the

year that the Empire Laundry was built, the federal

Bureau of Labor Statistics studied women workers in

power laundries in Milwaukee.

The

laundry industry in that city was felt to be representative

of other urban areas throughout the country. Of the

31 laundries in Milwaukee at that time, only 13 were

in buildings specifically designed for that purpose.

Others were located in reconstructed houses or modified

commercial buildings. Despite their relatively small

number, the 13 purpose-built laundries "employed

70 per cent of all the power-laundry workers in Milwaukee

and did approximately 80 per cent of all the laundry

work done in the city.

|