The New Richmond Laundry at 224 Pontius N is a Seattle city landmark, now almost buried beneath a hideous complex of office space and condos despite its official "historic" status. The initially landmarked building, however, was important for numerous reasons. At the time it won landmark status, it was the single working survivor of the Seattle steam laundry boom.

In 1999, the New Richmond was still a commercial laundry operating out of its original premises – albeit altered to reflect the industry's changing technology. As New Richmond Supply Laundry, it also owned the goods it laundered and leased: linens and working garb "supplied" to businesses and cleaned. This too was a continuous tradition in laundering.

The New Richmond had come to represent a Seattle laundry dynasty; its owners, the Tomlinson family, have been rooted in the business for over 40 years.

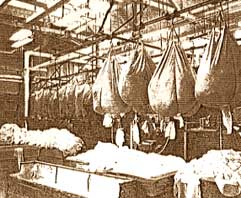

A

link in the unbroken chain of technological development at the New

Richmond Laundry

|

As was typical of many "Pacific laundrymen", they once controlled a number of different laundries (including the now-languishing Imperial). The Tomlinson connection to the name New Richmond dates to 1918 when Albert D. Tomlinson became involved with the laundry operating from the New Richmond hotel at 308 4th Ave S.

The family's connection to the historic building on Pontius N, however, dates only from their purchase of it in 1961. By this time, its history was already notable.

The initial two-story facility here was built in 1917 (after the laundry girls' early summer strike; permit #159091) as the Metropolitan Laundry. It was designed by the architect Max Umbrecht, a well-known name in Seattle history. The social statement made by his involvement is as interesting as Umbrecht's stylish architecture.

Asking such a well-known name to design one's laundry made clear the importance of a "laundryman" in his community and Umbrecht was commissioned by W.H. Weaver, an early participant in Seattle's laundry boom. Weaver owned his first power laundry, the Marine, by 1904. Five years later, power laundries had become the city's second-largest industry and he was one of those who reaped the benefits. Weaver's Metropolitan Laundry Company specialized in what was known as "the family bundle", rather than commercial, hotel or hospital laundry. In early 1914, Pacific Laundryman magazine cited this as a key to Weaver's rising fortunes; by February, they called Weaver and his partner. Charles F. Burrows, "perhaps the most optimistic laundrymen in Seattle" due to the "continuous growth" of the Metropolitan.

In 1915, the trade journal reported that Weaver and Burrows had set about establishing a branch of their business "in the new public market under construction on Yesler Way". Pacific Laundryman hailed "a laundry branch office in an establishment of this kind" as an ingenious "new idea in Seattle".

A year before the premises on Pontius were commissioned, however, the Metropolitan Laundry Company was also excoriated in the Seattle Union Record. Weaver and Burrows were cited, along with other laundry titans, as having "for years successfully blocked any and all attempts to organize the laundry girls of Seattle" (September 27, 1916, page 6).The Pontius premises post-date Seattle's 1917 laundry strike. Although it was involved in labor altercations, this plant built a notably steady and very successful business. Between 1923 and 1937, when laundering started to slow, it rose from Seattle's eighth-largest to its fifth-largest firm (Directory of Washington Manufacturers, 7th, 8th, 9th edition;. Greater Directory of Washington State Products, 10th edition).

By 1999, the venerable premises at 224 Pontius N embodied all the technological changes their industry had seen. As its 1999 Landmark Nomination stresses, it was sequentially altered from a dye works and steam-powered laundry into a gas-powered commercial supply laundry, a dry cleaning establishment (which, notably, specialized in rug cleaning), even, as the Seattle Times noted on July 9, 1914, remade as the hospital laundry of the University of Washington.

The 18 permits on file for all these alterations and expansions comprise a fascinating history. For instance: The Metropolitan Laundry Company's application to build on Pontius was granted July 13, 1917; by the following evening, 1,100 women laundry workers in the city were on strike. Earlier in June, alongside D.C. Keeney's Seattle Empire Laundry, the Metropolitan had been listed in the Seattle Union record as one of 17 "UNFAIR TRUST LAUNDRIES". Yet construction of the new plant proceeded apace, with the last recorded inspection necessary to opening made on November 20, 1917.

Significant alterations required by the laundry's success each tell their own stories. In 1925 (permit #247800 ) and in 1929 (permit #287581) came additions designed for the business by Ira S. Harding. As architect and builder of the 1914 Seattle Empire Laundry, few locals could better understand a power laundry. The alterations Harding devised were, respectively, a single-story garage to help with increasing deliveries and a "dry house". The latter would have been intended to increase the laundry's output of "finished" clothing, especially shirts.

In one of several inaccuracies and errors, the 1999 Landmark Nomination for the New Richmond fails to note anything relevant about Harding. It in fact incorrectly asserts that his 1929 addition (the dry house) was "unidentified".

Like all the alterations, it was in fact industry-specific. Subsequent permits detail a litany of necessary transformations. They include: the 1926 refitting of a chimney built in a hurry, "without permit" (permit #257735); then its shortening by over two feet in 1931 (permit #395998). The laundry gained another story in 1931 (permit #317656), was improved to meet mill classification in 1944 (#363172) and its structure was strengthened with steel in 1948 (permit #385254). Paras 3-9 on page 9 of the 1999 Landmark Nomination detail well the "kinetic" work environment of a laundry that had been in continuous operation, with continuous technological updates, for more than 80 years.

One of the most remarkable facts of this continuum is revealed on page 9 of the 1999 landmark nomination where it is stated that the New Richmond "currently employs around 70 people working in a variety of specfic tasks". The same statement could have been made as far back as 1921 - the staff was tallied at 70 people from 1921 until 1937 (Directory of Washington Manufacturers, 7th, 8th, 9th editions; Greater Directory of Washington State Products, 10th edition).

When Albert Tomlinson purchased the building in 1961, it was trading as the Pantorium Laundry (a homage to another former title, the Pantorium Dye Works). Tomlinson re-christened his purchase the "PRIM Laundry". According to the Tomlinson family, this name commemorated the first letter of each business Albert Tomlinson owned. A mural of the PRIM logo was still visible on the southern wall in 1999.

The Tomlinson family commissioned the 1999 nomination to rule out landmark status; they intended to replace the laundry building with a "new, multi-family structure". Thanks to their involvement its report contains valuable information about the laundry's latter days, as well as reproductions of unique historic photographs. But it was hardly written to enlarge the body of knowledge about Seattle's industrial industry.

Shortly after the designation of the New Richmond Laundry as a landmark, the laundry did remove its operations to new premises. According to Seattle Municipal Code, a landmark cannot be demolished. But it can certainly be disfigured. This building's sad fate incarnates Seattle's lack of respect for its own history, architecture and achievements. As with Seattle's "historic" 66 Belltown Lofts (the landmarked Seattle Empire Laundry). Both stand as hideous, disfigured testaments to the greed of developers - the modern equivalent, perhaps, of that greed which drove the "Pacific laundrymen".

|

back

to Seattle's Other Power Laundries

|